With the U.S. funded Marshall Plan to help rebuild Germany and Europe.

Germany was divided into four chunks, to be administered and by the major allies: The U.S., Britain, France and the Soviet Union. Its capital, too — Berlin, deep in the Soviet sector in the eastern part of Germany — was also partitioned into four sectors.

As long as food, clothing, coal for heating homes and supplies for rebuilding the country's ruined cities could move freely between sectors, there was no problem. But in June 1948, that freedom was threatened when the western allies introduced a new German currency that would address issues caused by a growing black market in the Soviet-controlled sector of Berlin.

On June 26, 1948, an angry Stalin ordered a halt to all freight and passenger traffic into and out of Berlin from the other sectors.

Allied air forces responded immediately, flying food and other supplies from bases in the U.S. and British sectors of Germany into Berlin's Tempelhof Airport and other airfields in West Berlin. Officially, the effort was named “Operation Vittles.” But history would come to remember it as the Berlin Airlift

The U.S. Air Force set up a complex pattern in which cargo planes would fly at five different altitudes — separated by 500-foot buffer zones — and 15 minutes apart. This meant planes could arrive in Berlin every three minutes. Experienced air traffic controllers were flown in from the states to keep everything running smoothly.

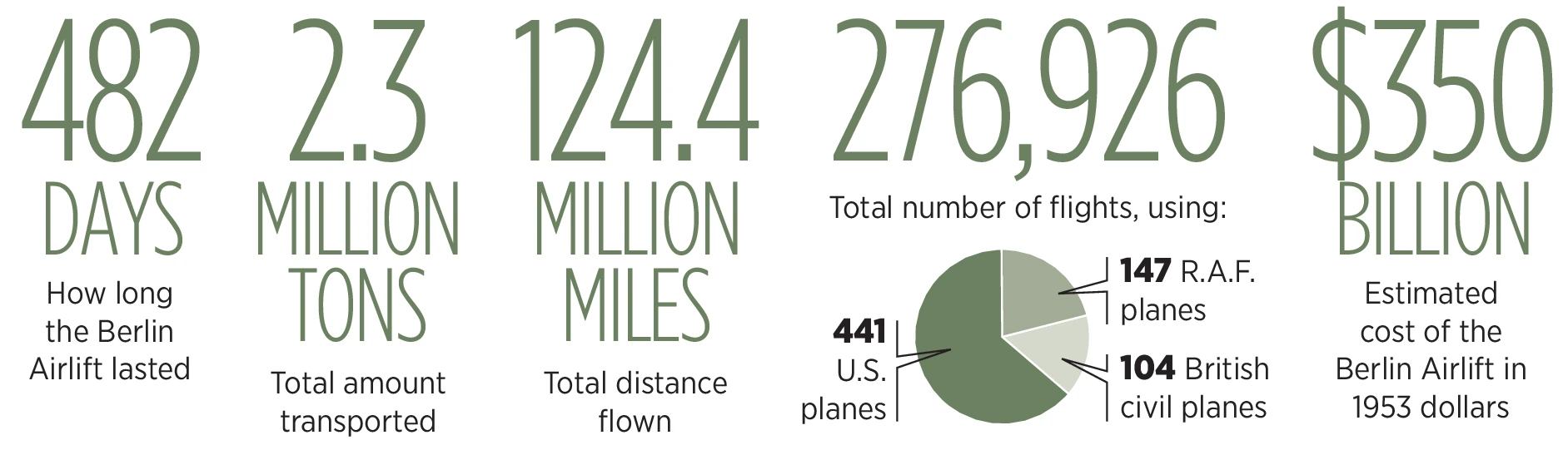

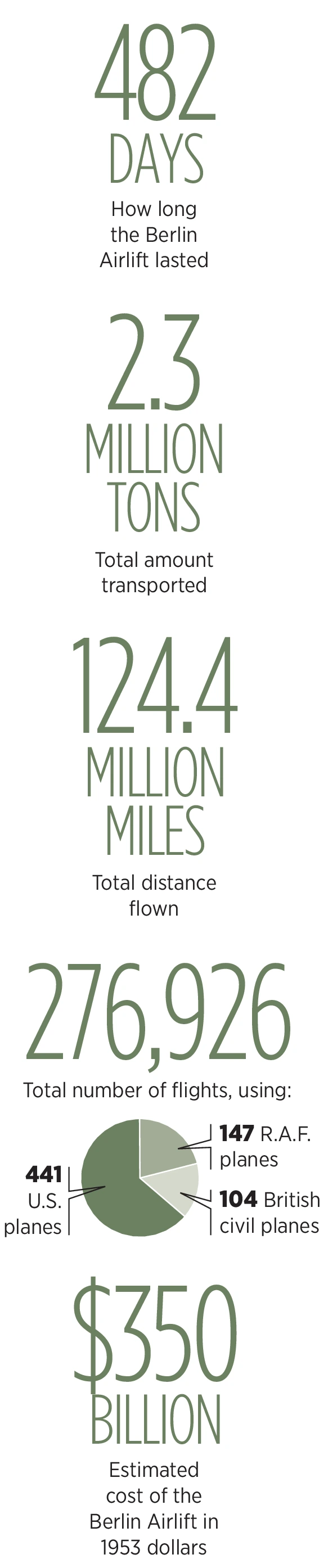

By the end of July, the airlift was delivering 2,000 tons of supplies every day. By the end of August, it was 3,000 tons every day. The U.S. Air Force celebrated Air Force Day on Sept. 18, 1948, by making a special effort to deliver nearly 7,000 tons to Berlin over 24 hours. So much coal piled up that civilians in West Berlin were given bonus rations.

That December, pilots flying out of the British sector organized an effort to deliver Christmas gifts to 10,000 children in Berlin.

At the end of February 1949, the airlift broke a record by delivering 44,612 tons in a single week. On April 16, the operation made another special effort — an “Easter Parade”

— which resulted in a new 24-hour record of 1,398 flights carrying 12,941 tons of supplies.

By this time, it had become clear to Stalin that the western allies weren't going away. Not only that, but a reciprocal blockade set up by the U.S., Britain and France was keeping important resources created in the rapidly rebuilding western Ruhr Valley — coal, steel, machine parts — from reaching East Germany and East Berlin.

Just after midnight on May 12, 1949 — 10 months and 16 days after it had begun — the Soviets lifted the blockade. The barriers along the autobahn were taken down and convoys of trucks streamed into Berlin.

Electricity was restored through the city. Residents lingered in front of shop windows displaying things they had not seen for months: cream cakes, butter, crusty bread, strings of sausages. The people of Berlin wept with gratitude.

Still, even as they cut down on the number of flights and began sending personnel back home, the western allies continued to stockpile food and material in West Berlin — just in case another situation arose. On Sept. 30, 1949, a load of coal was flown into Berlin for the 276,926th — and final — flight of the airlift.