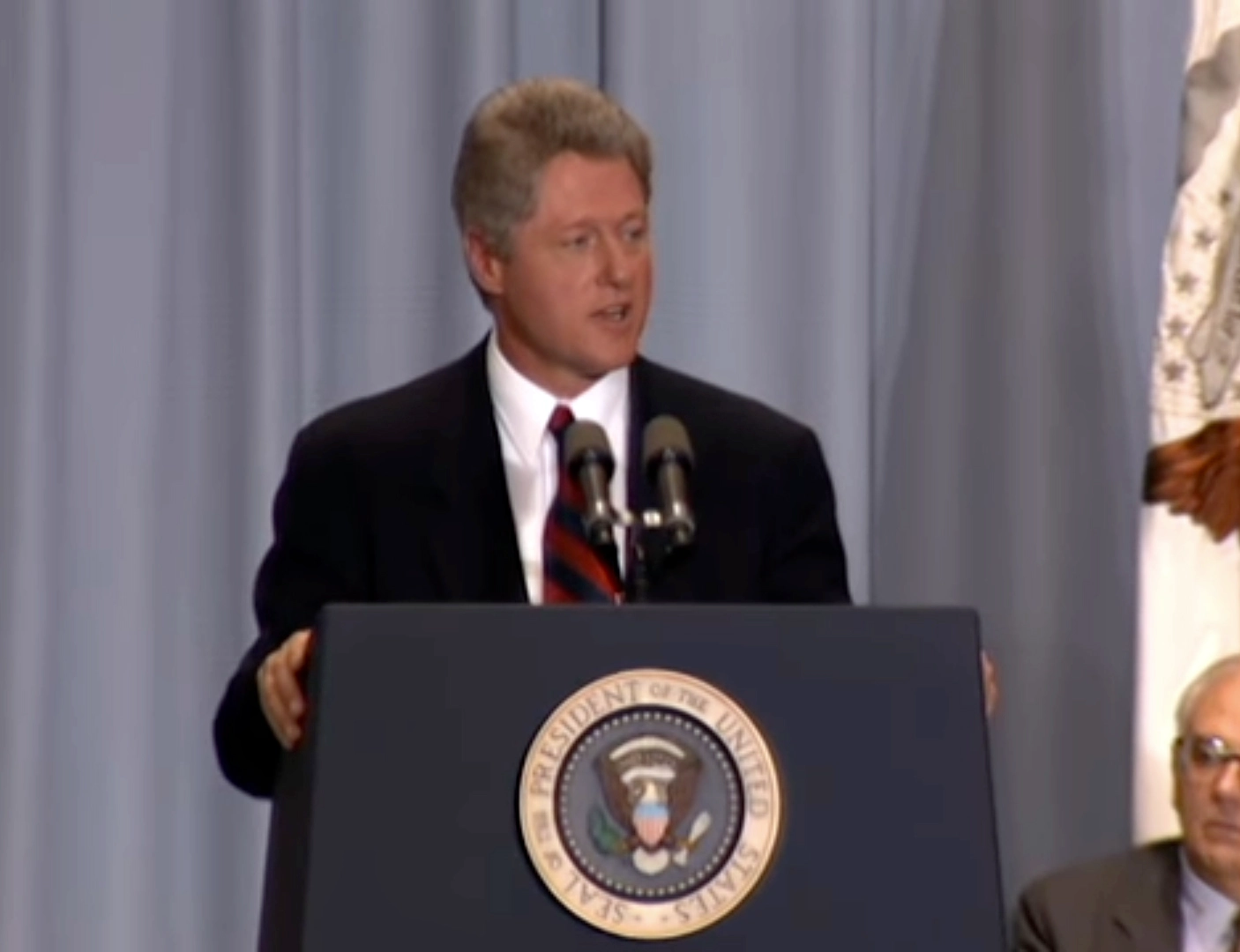

Thirty years ago Wednesday, President Bill Clinton announced an end to a longtime ban on gay men and women serving in the U.S. military. The new policy was a compromise that pleased neither conservatives nor gay rights advocates. But it was a step on a long road to today's military policy of inclusiveness and support of its LGBTQ+ members.

An Attempt To Honor A Campaign Promise

One of several issues raised during the 1992 presidential election was bringing an end to the military's longstanding ban on gays serving the military.

Every Democratic candidate — including the winner of that fall's election — had pledged to pursue change. And despite his efforts to keep his administration — and the media — focused on economic issues, the ban continued to be a hot topic.

Shortly after Clinton took office in January 1993, the New York Times reported that a possible change was “causing more heart-burning in the military than women in combat.”

Clinton called a meeting with his Joint Chiefs of Staff. They were against changing the policy but were also opposed to an idea floating around Congress, to reinforce the policy into federal law.

The chiefs acknowledged there were thousands of gay men and women serving with distinction in the military but letting them serve openly would be “prejudicial to good order and discipline,” said Colin Powell, Clinton's chief military adviser.

Clinton countered that it had cost the military $500 million over the past decade or so to kick 17,000 homosexuals out of the service and that polls showed that 60% of Americans favored relaxing the ban.

Powell argued for keeping the ban in place. He said that “sodomy” is banned by the Uniform Code of Military Justice” and that an “absolute right to privacy” does not exist for soldiers in close quarters.

“A possible solution,” Powell then offered, is that “we stop asking.”

Clinton put the final decision on ice for six months. When he issued the new policy on July 19, 1993, it was dubbed the “don't ask, don't tell” policy.

Retired general and former Republican Sen. Barry Goldwater wrote in support of the policy in the Washington Post: “You don't have to be straight to shoot straight.”

An Imperfect Compromise

“If you say you're gay, it's presumed that you intend to violate the Uniform Code of Military Justice,” was the way Clinton himself, in his 2004 memoir, described the compromise. “You can be removed unless you can convince your commander you're celibate and therefore not in violation of the code.

“But if you don't say you're gay, the following things will not lead to your removal: marching in a gay-rights parade in civilian clothes, hanging out in gay bars or with known homosexuals, being on homosexual mailing lists and living with a person of the same sex who is the beneficiary of your life insurance policy.”

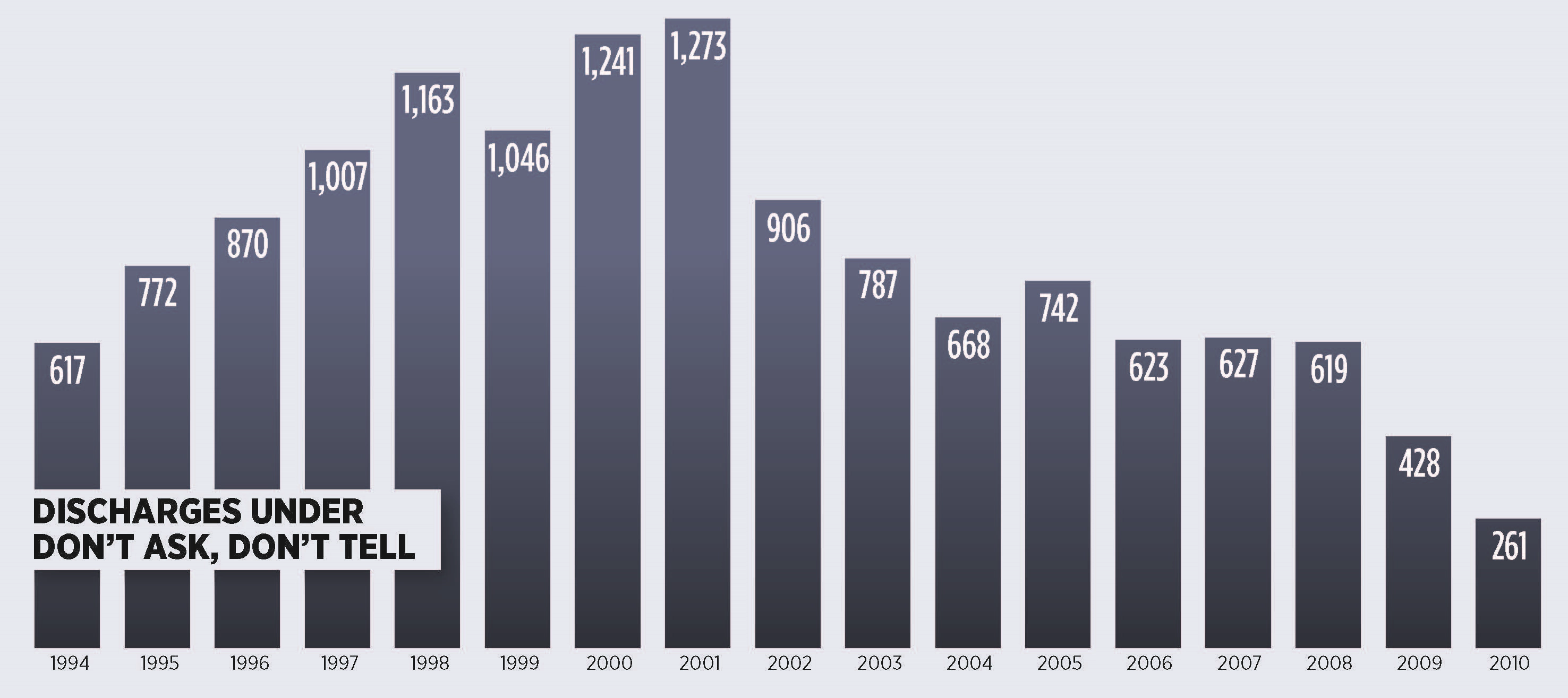

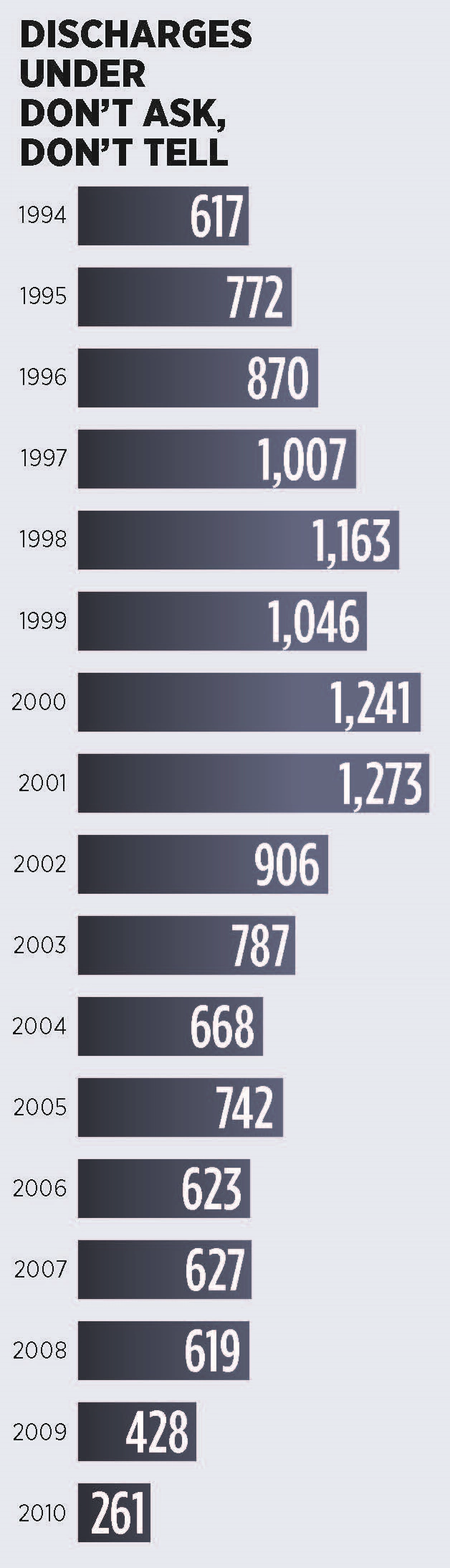

It was indeed a compromise — and a failed one at that, Clinton wrote. “Many anti-gay officers simply ignored the new policy and worked even harder to root out homosexuals, costing the military millions of dollars that would have been far better spent making America more secure.”

In 2005, the General Accounting Office estimated it cost the government $10,000 for every service member who was discharged under the don't ask, don't tell policy. A year later, another study by researchers at the University of California, Santa Barbara found the actual number was closer to $37,000 per service member.

Even though don't ask, don't tell had not required members of the military to be discharged dishonorably, many were anyway. This made them ineligible for veterans benefits.

In his State of the Union address on Jan. 27, 2010, President Barack Obama promised to work with the military and with Congress to “repeal the law that denies gay Americans the right to serve the country they love because of who they are.”

A Repeal Of The Policy, 18 Years Later

Democrats eager to eliminate don't ask, don't tell tacked a provision to repeal the policy onto its annual defense budget legislation in May 2010. Sen. John McCain, who stressed that military leaders supported DADT, led a filibuster against the budget until the repeal was removed.

Democrats tried again that winter with a stand-alone bill. This time, the repeal passed both houses. President Barack Obama signed the bill into law on Dec. 22, 2010. The repeal went into effect on Sept. 20, 2011.

“The repeal of DADT gave LGB service members the freedom to serve without having to hide an essential part of themselves,” wrote Kayla Williams, assistant secretary for public affairs in the Veterans Administration's Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs.

She is herself a “bisexual veteran,” she said.

“It also recognized what so many of us already knew to be true: That one's ability to serve in the military should be measured by character, skills and abilities, not who one loves,” Williams wrote.

In June 2012, the Department of Defense officially began observing Pride Month. In February of the next year, the DoD extended benefits to same-sex domestic partners and children of same-sex domestic partners.

In September 2021, the VA announced it was clarifying its policy on all service members discharged “due to sexual orientation, gender identity or HIV status” who may be eligible for VA benefits like home loans, pensions, health care and burial benefits. Those who had previously been discharged or denied benefits were encouraged to reapply.

A 2016 report by the Associated Press said that less than 8% of veterans expelled under DADT had applied to upgrade their discharges or to strip references to sexual orientation from their record. The policy change was aimed at encouraging more to apply.

This edition of Further Review was adapted for the web by Zak Curley.