Survey finds 3,300 homeless students in Spokane County

The homeless problem in Spokane can’t be measured by the sleeping bags in downtown streets and alleys.

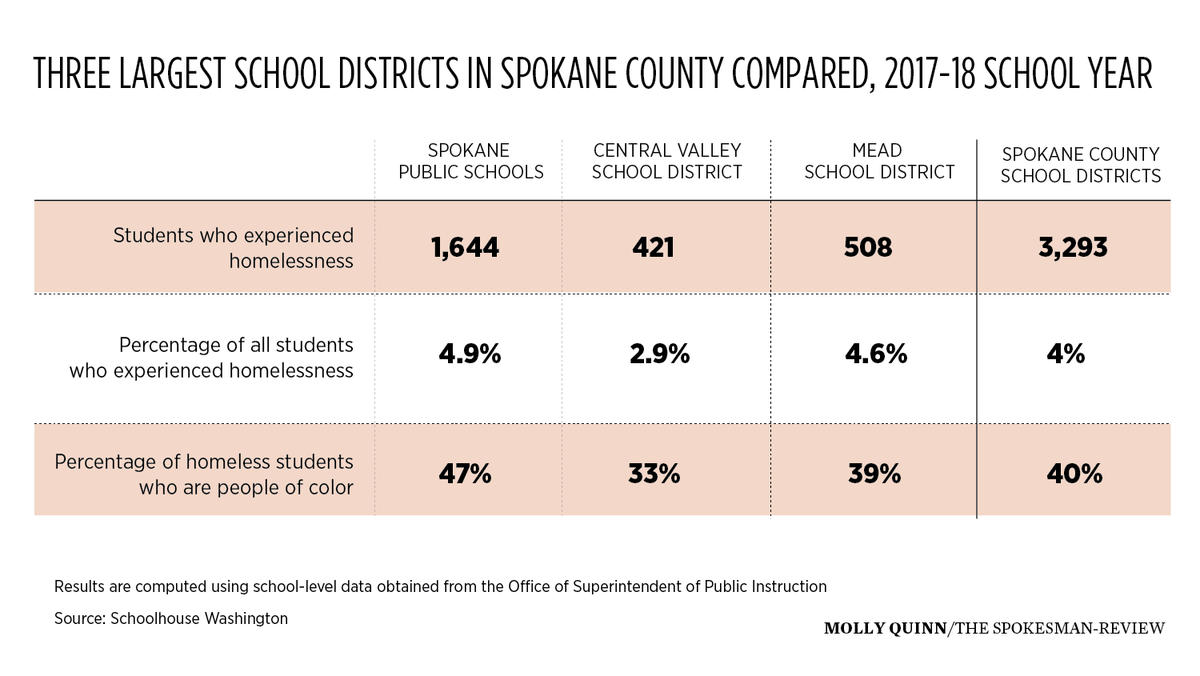

Rather, it’s defined by empty stomachs, truancy and the prospect of a desolate future for roughly 3,300 homeless children in Spokane County, according to a comprehensive study released Monday.

“And it’s getting worse,” said Lori Wyborney, the principal at Rogers High School.

Relatively few of those kids are squatting on the streets of downtown Spokane. More often they’re “doubling up”: living in an aunt’s apartment in Hillyard or in a cousin’s single-wide in the tiny district of Deer Park – home to 96 homeless students.

Many are staying at a friend’s house and crashing academically, according to the 104 pages of findings released by Building Changes, a Seattle-based nonprofit that works with government and homeless service providers, including schools, to end youth and family homelessness.

In Spokane County, 1 student in 25 was homeless during the 2017-18 academic year, according the the study.

Mostly they’re invisible, at least to federal statisticians, who employ a narrow definition of homelessness that includes only people who are living in shelters, motels or on the streets.

Last winter, the Point in Time Count survey found 1,309 homeless people across the county.

The problem is far greater, according to the Building Changes survey, which shows 3,293 homeless students in grades K-12.

Of those, 78% are living “doubled-up” at another home; 4% reside in hotels or motels; 12% in shelters; and 6% – or about 200 – unsheltered.

Countywide, those 3,293 children are facing profound disadvantages compared with students who have a permanent home.

The report showed 59% regularly attend school (defined by the state as missing 17 days or fewer in a year).

Predictably, they’ve fallen far behind their peers in the classroom.

In Spokane County, about 34% of homeless students are meeting proficiency standards in English. Just 26% are meeting the math criteria. For housed students, those numbers are 66% and 56%.

By the time they reach high school, the damage is done.

“We get them at the tail end,” said Wyborney, who recalls with pride the rare student who can overcome those handicaps.

One of them, Alissa Scott, is now at Eastern Washington “with the dream of becoming a nurse.” Six years ago she was removed from her parents’ custody and almost flunked out as a freshman.

Homeless for much of her high school career, Wyborney described Scott as “that special kid who said ‘I’m not going to put up with this and I’m going to go down a different path.’ ”

As for the others, many of the 1,200 homeless high school students in Spokane County find it easy to take a look around a tough situation at home and say “screw this, I’m outta here,” Wyborney said.

“Let’s not forget that the path to homelessness is generally very ugly,” Wyborney said.

But while many homeless teens flee abuse, drugs and neglect, others are cast off by parents and guardians who can’t keep up with rising rents.

“We hear it all the time, kids saying ‘I get along with my parents, but they say they can’t afford me anymore,’ ” Wyborney said.

In other cases, parents moved to another part of town to save on rent, leaving their teen to choose between family and staying at the same school. Many choose the latter and end up couch-surfing with friends and relatives.

Not surprisingly, 36% of homeless students in Spokane County fail to get a diploma. That perpetuates a cycle of low-level employment in a city “where the jobs are mostly going to be hourly-wage jobs,” Wyborney said.

Statewide, the problem is roughly the same as in Spokane County, with 3.7%, or 42,599 students reported as homeless. That number puts Washington with the seventh highest number of homeless students among the states.

However, the state’s largest school district, Seattle Public Schools, faces a particularly high rate of child homelessness: 7.5%, or 4,388. More than one-third of those live in shelters.

Other statewide findings revealed both encouraging and discouraging trends since a similar survey from 2015: