Outdoor writing contest: A Walk in the Woods

Wynn knew he was nothing like his brothers and sisters. They were older, always helping their father on the farm and their mother in the house. They did the things dutiful children ought to do. Certainly, none of them would be so foolish as to venture into the Cursed Woods.

Mothers warned children to stay far away from the Woods, farmers blamed them when livestock was killed. People who went into the woods came out changed, if they came out at all. Every passing traveler heard the warning, and every local knew the consequences of setting foot inside.

Wynn wasn’t a superstitious person on most counts. He’d picked up habits from his mother – throwing salt over his shoulder when he spilled some, leaving a dish of cream outside the door for faeries – but these were trivial gestures. He was less inclined to superstition where the Woods were concerned.

When his mother needed a potion ingredient that could only be found in the Cursed Woods, his siblings had provided various excuses on why they couldn’t search for it. But Wynn, the youngest, always teased for being soft and cowardly, jumped at the opportunity to see whether the stories about the forest were true. He still feared what might lurk inside the Woods, but curiosity overpowered his foreboding.

For all the dire warnings Wynn had heard, the Cursed Woods didn’t seem very cursed. Trepidation prickled at the back of his neck as he entered, but it was soon replaced by a dreamlike calm. Golden sunbeams pierced the canopy – the trees themselves seemed to hold their breath. The leaves had changed early this year, and the full spectrum of autumn was on display.

The silence calmed Wynn, that feeling of knowing he was the only human for miles. The wind murmured in the trees; distant birds sang. No matter how hard he tried, he couldn’t find this sparkling solitude anywhere else, in the village or on the farm.

As Wynn wandered, he searched for the herb his mother needed among the towering oaks and beeches. Every so often he caught a glimpse of an animal – the red breast of a robin, the too-clever eyes of a fox. Most of them blended in with the foliage.

Wynn stopped short when he saw a flash of black amidst the sea of russet and brown.

At first, he thought it was his imagination. But then he saw it again out of the corner of his eye. He turned. A few feet away lay a great, black stag.

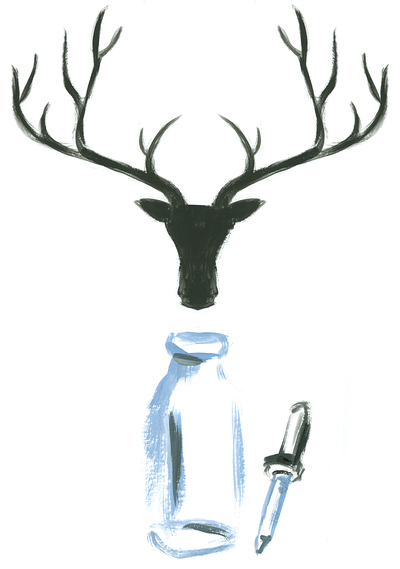

He blinked, sure his eyes were deceiving him. But there it was. Massive, curling antlers, eyes sparking with intelligence, fur as black as the potion his mother brewed for him when he couldn’t sleep. It looked like something from a faerie tale, a fragment of the night sky fallen and brought to life.

Wynn stepped closer. He didn’t dare draw breath for fear of scaring it. With every step he took, he imagined it darting away, never to be seen again. But it didn’t move as he drew nearer. It just lay on its side, eyes fixed on him. It was obvious something was wrong.

That was when he saw the blood.

It was almost invisible against the stag’s coat, a slight sheen that could have been water. But when the light shifted, Wynn saw it for what it was. He couldn’t even tell where it was coming from. It felt wrong, that such a magnificent creature could be tainted this way.

Wynn drew closer to ascertain whether it was the stag’s blood or the blood of another animal. The stag’s chest rose and fell rapidly, like it had been running. Even sprawled out on the ground, likely injured, it gave off an aura of immense power.

Wynn dropped to his knees before the stag, hands held out palm-up to show he meant no harm. Finally, he saw the hunter’s trap clamped around the stag’s front leg. Its metal jaws gleamed, sawing through flesh and muscle with the power of something that could only have been engineered by man.

Wynn winced as if the trap had ensnared him instead. He reached out and laid a hand on the stag’s heaving shoulder. A shudder went through the animal, but it didn’t pull away. Instead, it seemed relieved. It closed its eyes; when they opened again, they were fixed on Wynn.

Wynn stroked the stag’s thick fur, somehow both rough and soft. Carefully, he moved his hands to the trap. With effort, he pried it open and pulled it away. He barely managed to get his own fingers out of the way before the trap snapped shut again.

Both Wynn and the stag breathed a sigh of relief.

High in the trees, a bird sang a melody Wynn knew but couldn’t put a name to.

Then Wynn’s brain seemed to skip. One second the stag was there, the next a boy lay in its place.

He was pale, taller than Wynn, with dark hair the color of the stag’s coat. His eyes were just as dark. His bone structure was alien and angular, and the tips of his ears formed sharp points. Still, he might have seemed human if not for the antlers curling from his forehead. They were small, but otherwise identical to those of the stag, furred with moss and lichen.

The boy wore nothing but a pair of pants, so tight that any scrap of modesty was lost. Under different circumstances, Wynn might have been embarrassed – he’d seen worse on the farm, but he’d always been the most prudish of his siblings. Now, all Wynn could focus on was the blood smeared across the boy’s arm.

“Thank you,” the boy said. His voice was silvery, with an accent Wynn couldn’t place.

The boy took an object from his pocket and dropped it into Wynn’s palm – an arrowhead, roughly hewn from crystal, on a silver chain. Without another word or backward glance, the boy turned and vanished into the mist.