Prosecution rests in Enron trial

HOUSTON — Federal prosecutors rested their fraud and conspiracy case Tuesday against former Enron Corp. chiefs Kenneth Lay and Jeffrey Skilling and dropped four counts against them to streamline an already complicated case.

The defendants appeared undaunted after almost two dozen witnesses bolstered the government’s claim that they committed crimes at the energy trading company before it sought bankruptcy protection in December 2001.

“We’re looking forward to getting on the stand and getting our case out there — the positive case,” Lay told reporters outside the federal courthouse in Houston.

Their defense teams will begin presenting their case in the premier trial to emerge from Enron’s rubble on Monday, but other witnesses are likely to be overshadowed by the main event, when Lay and Skilling take the stand.

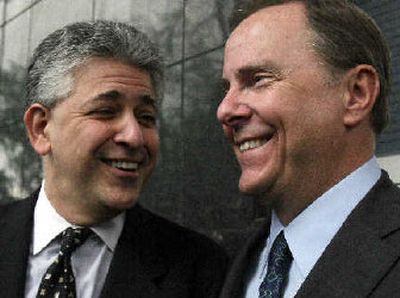

“We are anxious to get our story told,” said lead Skilling lawyer Daniel Petrocelli, his client at his side.

Prosecutors declined comment, as is customary during a high-profile trial.

Lay and Skilling will enter the defense phase a little lighter because U.S. District Judge Sim Lake approved a government request to drop several charges against them for which it had presented no evidence. Two counts of securities fraud and one count of lying to auditors pending against Skilling were dropped, leaving 28 criminal counts against him; and a single count of securities fraud against Lay was dropped, leaving six in his case.

Lake denied routine requests from the defense for acquittal.

The dropped counts against Skilling stemmed from allegations the former chief executive signed a fraudulent quarterly report submitted to the Securities and Exchange Commission; lied about Enron’s health during a first-quarter earnings conference call; and signed a statement to auditors that vouched for fudged financial statements.

The count against Lay that was dropped grew from allegations the company founder lied to analysts about Enron’s finances during a conference call.

Lay also faces a separate case related to his personal banking. In one count of bank fraud and three counts of lying to banks, prosecutors allege he obtained $75 million in loans from three banks and then reneged on an agreement with the lenders that he wouldn’t use the money to carry or buy Enron stock on margin. That case will be tried without a jury before Lake, beginning while jurors in the current Enron trial begin what are expected to be lengthy deliberations.

Prosecutors say Lay and Skilling repeatedly lied about the energy company’s financial health when they allegedly knew accounting maneuvers propped up an image of success.

The two men counter that the only fraud at Enron was committed by a few employees who skimmed money for themselves from secret scams, including former Chief Financial Officer Andrew Fastow.