Shifting Gere

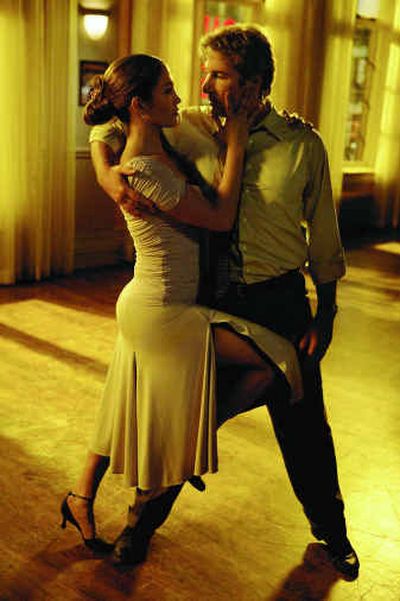

Nirvana ain’t easy. Richard Gere has spent more than 25 years journeying toward that state of perfect blessedness. But the last few weeks have been making progress pretty difficult. First, “Shall We Dance?” co-star Jennifer Lopez decided to let him do most of the work publicizing the film, which opened Friday. Then Gere took a fall off his horse, breaking his hand. The heavy Tibetan prayer beads he wears wound around his right wrist, and all those sacred teachings about the nature of earthly suffering, don’t seem to be lifting his mood. But he brightens when he talks about his new movie. “This is not a deep, emotional film,” Gere says, running his hand through hair the color of antique silver. “But there’s a sweetness to it, and a truth to that sweetness.” The sweetness comes from the film’s source, a 1996 Japanese hit about a shy businessman who rejects his country’s conformity by taking dance classes. The truth, Gere hopes, comes from the new translation, which moves the story to Chicago and has Gere’s vaguely unhappy hero abandon his commute to learn the waltz.

“A man’s going home and suddenly decides to get off the train,” the 54-year-old actor says. “It’s about opening up. It’s about listening to this mysterious drive in us all.”

Gere’s own drive – which led him from college to off-Broadway theater, sexy Hollywood movies and a passionate commitment to Buddhism and Tibet – is a little mysterious, too.

It began in Syracuse, N.Y., where Gere grew up.

“We did school plays and sang in the church choir and we all played instruments,” he says. “To this day, every day, I thank my mother and father for those music lessons when we were kids. Because there were five kids and we were not a wealthy family.”

After high school, Gere went off to the University of Massachusetts, where he took some philosophy courses.

“My grades were pretty terrible,” he admits. “But acting had something for me, touched something in me.”

After auditioning for a part in a play on Cape Cod, he says, “I remember … getting the call in my dorm room saying ‘You got the job.’ And I knew, this is it – my life has started.

“And so,” he says, “I ran off to join the circus.”

Gere’s father, an insurance salesman, wasn’t thrilled to hear that his 19-year-old son was dropping out. He probably grew less thrilled as Gere’s travels took him to Seattle, San Francisco and even, briefly, a rock ‘n’ roll commune.

“I was a pretty standard-looking hippie at that point,” Gere remembers. “Long hair and a motorcycle jacket. So I did a number of rock musicals, and I was making some money … . I was getting some good parts, and there was a reputation that was starting to evolve.”

That reputation wasn’t always flattering.

“I’ve known him forever, although we hadn’t worked together before,” says Susan Sarandon, his other co-star in “Shall We Dance?” (She grins, and adds: “I never even slept with him – how’d that happen?”)

“I think he’s much … mellower now,” she says. “And you know, at this age, that doesn’t seem like such a bad word anymore.”

The mellowness, though, comes and goes.

Allude to “Looking for Mr. Goodbar” really taking him to a new level in his career, and Gere’s instantly dismissive.

“It had happened long before that,” he says, though previously he had only bit parts in movies like “Baby Blue Marine.” “I was already doing really interesting plays in New York. I could have kept going at that and made a good living.”

In 1978, the year after “Goodbar,” Gere co-starred in Terence Malick’s cult epic “Days of Heaven.”

“I had seen ‘Badlands,’ his first film, and I was quite taken with that,” Gere says. “I thought this is someone I can work with, this is someone special. And then when ‘Days of Heaven’ came along, I knew, clearly, that my life was going to change.”

Gere – never the best judge of material – followed that film with “Bloodbrothers,” based on the Richard Price novel, and the wartime flop “Yanks.”

But then, in 1980, John Travolta dropped out of “American Gigolo,” and Gere got a career-defining role as the smug, Armani-clad, multisexual prostitute.

When “An Officer and a Gentleman” followed in 1982, featuring Gere romping in bed with Debra Winger, his sex-symbol status was assured – as well as his image as someone who could leave a leading lady in tears.

“They’re two very strong people who had their own perspectives on things,” says “Officer” director Taylor Hackford. “But believe me, they created great chemistry. You don’t necessarily have to love somebody to create sexual tension.”

More than 20 years later, Hackford is still proud of that film, and admiring of Gere’s emotionally naked performance.

“He was always there, always totally committed,” he says. “My sense of Richard is that too often people just look at him and settle for that beautiful exterior and don’t ask him to go any deeper. You ask him, though, and he’ll go there for you.”

Repeat the compliment, and Gere only bristles a bit.

“Well, I know what he’s saying, but that’s also a bit naive,” he says. “Some parts don’t require you to do all that. How many great parts in movies have that great bravura (quality) — there just aren’t that many around. De Niro, how many have there been for him?”

There weren’t that many for Gere as the decade went on. “An Officer and a Gentleman” was followed by the ill-advised “Breathless” remake and a misfired Graham Greene adaptation, “The Honorary Consul.” “The Cotton Club,” in 1984, was a legendary disaster on several levels, and the biblical “King David” was roundly ridiculed.

“It’s very difficult to find good roles,” Gere says now, “and the competition for them is extremely high. So you do the best of what’s out there, and you fulfill the requirements of it. You rise to the necessity of the character. … It’s very easy to destroy a piece by giving too much.”

As the ‘80s wound down, Gere was still coasting. But then in 1990, “Internal Affairs” gave him the chance to play a smirking, arrogant bad cop, and “Pretty Woman” gave him a more sophisticated, romantic image – smoother and more polished than the rough-trade Romeos he’d once played.

Since then he has continued to recharge his career every few years – following up five years of flops (remember “Sommersby,” “Mr. Jones,” “Intersection” and “First Knight”?) with the smart “Primal Fear”; coming back from “Autumn in New York,” “Dr. T & The Women” and “The Mothman Prophecies” to hit with “Unfaithful.”

“I’m thankful that there have been enough good parts around, and I’m very lucky that they’re here now,” Gere says. “I didn’t realize I’d last this long.”

It was a tap dance routine in “Chicago” that made director Peter Chelsom want Gere for “Shall We Dance?”

“It’s not that I saw a dancer in that film,” Chelsom says. “I saw a man who was willing to learn – and that was crucial.

“It would have been really worrying to me to have the part of a man learning to dance played by someone who was lazy. Richard’s not afraid of hard work, or reluctant to be just another member of the company.”

That is clear in his work. Whatever on-set relations are like, Gere consistently ends up making his leading ladies look good – whether it’s Winger in “Officer and a Gentleman,” Diane Keaton in “Goodbar,” Julia Roberts in “Pretty Woman,” Diane Lane in “Unfaithful” or even Jennifer Lopez in “Shall We Dance?”

“I like people to be good,” Gere says. “I like the work to be good, so I take care to make it a loving experience. And I genuinely love actors, and I genuinely love women.”

He’s been married to actress Carey Lowell, the mother of his son, Homer, since 2002. His first wife was model Cindy Crawford.

Despite the beauties on his arm, though, Gere’s private life has always inspired sly speculation; his long bachelorhood, coupled with a fearlessness in playing gay or bisexual characters, only fueled the rumors.

“I really don’t pay any attention to it,” Gere says of the constant publicity, although a decade ago he and Crawford paid for a newspaper ad to assert their heterosexuality.

“In the beginning, when all of a sudden that kind of (media attention) happens to you, you have an animal response to it: You run. You show your teeth, you scare them off, and then you run. But at this point, I don’t even think about it, to tell you the truth.”

Mostly, what Gere thinks about is Tibet, and the efforts of the people in that brutally occupied country to find some measure of freedom.

He has spearheaded a charity and raised money; he has sponsored visits, narrated documentaries and even made a thriller about the viciousness of the Chinese government, “Red Corner.”

All of it comes from his long and serious devotion to Buddhism and the Dalai Lama, whom he respectfully refers to as “His Holiness.”

“I was raised Methodist,” Gere says. “My parents and the people that I knew … were incredibly generous and open and heartfelt and charitable and compassionate. But what I found lacking was this kind of penetrating curiosity about the nature of things, the nature of reality. What is the nature of the mind itself? What is the nature of the relationship between mind and reality?”

Gere’s public devotion to the faith has helped popularize it in Hollywood. It has also, occasionally, led to sniping from cynics who question any movie star’s sincerity, or from scholars who point out that the Buddhism that’s popularized by celebrities often glosses over some of the faith’s more conservative statements on sexuality and abortion.

“I don’t know those passages myself,” Gere says. “I know that some of them are controversial. I think much of the Bible can be quoted to serve a variety of purposes, too.

“I do know that I’ve never been in a situation with genuine Buddhists that wasn’t all-inclusive. From beings on other planets to insects here on Earth – there’s this deep belief that everything that lives is equal … . It’s about the joining of a compassionate heart to a penetrating wisdom.”

Gere hasn’t reached a blissful state of perfection yet. And there are days – when his hand’s in a cast, when his leading lady isn’t doing press – when that goal seems a long way off.

But he’s trying.